Session Details – Backyard Imaging of M51

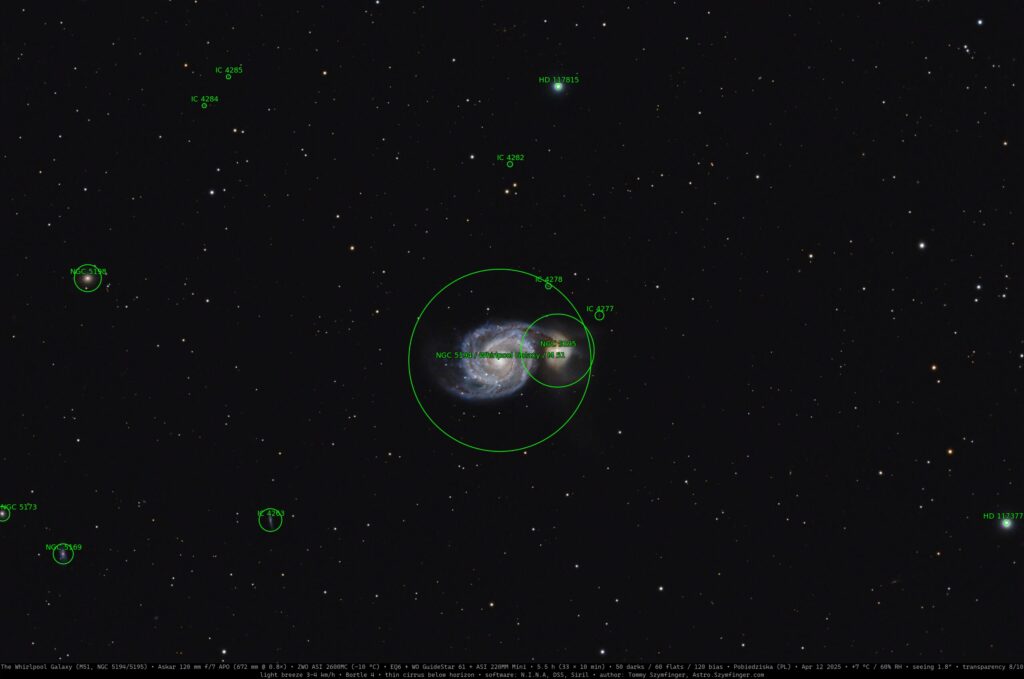

This particular image of M51 was captured from my own backyard observatory, located under Bortle Class 4 skies — dark enough to reveal the galaxy’s core and inner arms visually through the telescope, yet still with some light pollution glow on the horizon. The night offered excellent transparency (around 8/10) and steady seeing (measured at ~1.8 arcseconds), which allowed the finer dust lanes in the spiral arms to come through sharply in the final image. The ambient temperature during the session hovered around 7°C, with relative humidity at about 60%, preventing excessive dew formation. A light breeze of 3–4 km/h kept the optics cool and stable, and thin cirrus clouds stayed well below the western horizon for the entire imaging run.

For this project, I used my standard deep-sky imaging setup:

- Telescope: 120 mm f/7 apochromatic refractor with a 0.8× reducer (effective focal length: 672 mm)

- Camera: cooled ZWO ASI 2600MC at –10°C

- Mount: EQ6-class equatorial mount with autoguiding via a 61 mm guide scope and mono guide camera ZWO ASI 220MM Mini

- Total Integration Time: 5.5 hours (33 × 10-minute subs) over a single night

- Calibration Frames: 50 darks, 60 flats, 120 bias

Even with a shorter total integration, careful calibration and processing brought out not only the bright spiral arms but also hints of the faint tidal streams around NGC 5195. The galaxy’s subtle blue star-forming regions and the warm golden tones of its core stand out clearly against the dark background, thanks to good sky conditions and precise guiding.

From a personal perspective, this session was a reminder of why I love backyard astrophotography: even without traveling to remote locations, it’s possible to capture deep, detailed images of galaxies tens of millions of light-years away — all while listening to the quiet sounds of the night and occasionally sipping a hot coffee between exposures.

And now, let’s dive a bit into the theory…

The Whirlpool Galaxy (catalogued as Messier 51a, NGC 5194) is one of the most photographed galaxies in the night sky — and for good reason. Situated approximately 27 ± 1 million light-years away in the northern constellation Canes Venatici, M51 is a prime example of a grand-design spiral galaxy, where the spiral arms are not just visible, but sharply defined and symmetrical. For astrophotographers, this makes it a dream target: aesthetically striking, scientifically fascinating, and accessible with amateur equipment under the right conditions.

Basic Facts and StructureType:

SA(s)bc pec (spiral galaxy with well-defined arms, peculiar due to interaction)

Diameter: ~76,000 light-years (about 70% of the Milky Way’s size)

Mass: ~160 billion solar masses

Right Ascension: 13h 29m 52.7s

Declination: +47° 11′ 43″

Apparent Magnitude: ~8.4 (bright enough for small telescopes)

Surface Brightness: ~13.5 mag/arcmin²

Radial Velocity: ~600 km/s (moving away due to cosmic expansion)

M51’s most distinctive feature is its close gravitational interaction with its smaller companion galaxy, NGC 5195 (Messier 51b). The two are locked in a cosmic dance that has been ongoing for hundreds of millions of years. This interaction compresses gas and dust in M51’s arms, triggering bursts of star formation and enhancing the spiral structure — a process that can be beautifully captured in long-exposure astrophotography.

Astrophotographic Challenges and Rewards

M51’s bright core and inner arms are relatively easy to capture with exposures of just a few minutes using moderate apertures (e.g., 80–120 mm refractors or 8”–10” reflectors). However, to record the faint outer tidal streams, stellar plumes, and Hα emission regions, integration times of 10–20 hours or more are often necessary, especially in light-polluted skies.

Astrophotographers using narrowband Hα filters can highlight active star-forming regions scattered along the arms, while broadband RGB imaging brings out the galaxy’s soft blues and warm yellows — the signatures of young hot stars and older stellar populations. Advanced processing can even reveal faint hydrogen filaments extending well beyond the main disk, remnants of past gravitational encounters.

Scientific Relevance

M51 serves as a natural laboratory for astronomers studying:

- Galaxy interactions — providing real-time evidence of how gravitational forces reshape galaxies.

- Star formation — its spiral arms contain massive HII regions, some hundreds of light-years across.

- Dark matter — rotational velocity curves suggest that M51, like most galaxies, is embedded in a massive dark matter halo.

Radio observations show dense molecular clouds in the arms, while ultraviolet imaging reveals clusters of newly formed, massive stars. X-ray data from Chandra has detected black hole candidates and supernova remnants within M51.

A Historical Note

Charles Messier discovered M51 on October 13, 1773, describing it as a “faint nebula” without recognizing its spiral nature. That discovery had to wait until 1845, when Lord Rosse used his 72-inch “Leviathan” telescope to reveal its spiral arms — one of the first galaxies ever identified as such.

Why It Captivates Astrophotographers

- Visual Impact: Perfectly framed spiral arms, visible even in moderate amateur telescopes.

- Astrophysical Drama: An ongoing galactic interaction frozen in time for us to observe.

- Technical Benchmark: Imaging M51’s faint extensions is a test of both equipment and post-processing skill.

Whether captured from a backyard observatory under Bortle 5 skies or remotely from a Bortle 1 desert, M51 offers both beauty and scientific intrigue. Its mixture of bright structure and faint, elusive details makes it a long-term favorite — one you can revisit year after year as your skills and gear evolve.